Michael Oher may be the only Super Bowl champion to be more famous for being a character in a movie than, well, being a Super Bowl champion football player.

After all, it’s hard to outshine Sandra Bullock.

Before Oher spent eight years in the NFL, he was one of the subjects of acclaimed author Michael Lewis’ 2006 book, The Blind Side: Evolution of a Game, and then the sole focus of its big-screen adaptation, The Blind Side. The movie, written and directed by John Lee Hancock, traced Oher’s journey from homeless teenager to Division I All-American left tackle for Ole Miss. A smash hit that made over $300 million at the box office, the film won Bullock an Oscar but took some liberties with the particulars of Oher’s life story. In some ways, the real story is even more amazing than what was shown in the movie.

Oher was born in 1986, right smack in the middle of the crack cocaine epidemic that swept the United States’ inner cities. He was one of 12 children born to a mother who had fallen victim to the cheap and ultra-addictive narcotic, which set him along a troubled path from the start. His father disappeared early on, while his mother, Denise, struggled with addiction for many years.

“When my mother was off drugs and working, she would remember to buy groceries and there would be a mad scramble to grab whatever you could before anyone else got to it,” he wrote in his 2014 memoir. The problem was that she was rarely off drugs and working, so Oher was a nomad from an early age. Child services removed him and his siblings from their mother’s home when Oher was at the tail end of first grade, and he bounced around between foster families, friends’ couches and wherever else he could find a warm place to rest his head.

With little adult supervision or stability, Oher barely made it to school — he repeated both first and second grade, attended nine different schools over the course of 11 years and missed dozens of school days per year even when he was passed along to the next grade. The most stable home he had was in a housing project called Hurt Village, where he lived from 11-years-old until he began high school.

By the time he was 15, Oher was bunking up with a local athletic program director named Tony Henderson, who had an extra room in his house. Oher was already 6-foot-5-inches and 350 pounds, which made him a prime recruit for drug dealers seeking some muscle. He was less of a desirable prospect for prestigious private schools, but when Tony took his son Steven to the local Briarcrest Christian School, Big Mike, as he was called, tagged along for the ride anyway.

“He wasn’t no trouble kid, nothing like that, you know?” Henderson later told ABC News. “He was real quiet, you know, and just stayed to himself.”

He was so quiet, in fact, that Briarcrest’s admissions team couldn’t really find a reason to admit him, let alone offer him a scholarship. Having spent his life just trying to survive, getting into an expensive private school wasn’t really on Oher’s radar. He barely spoke during interviews, his reading comprehension level was closer to elementary school and tests showed he had an IQ that barely cracked 80.

Still, the school football coach was interested in Oher, not just as a prospect for the team but as a redemption story. This was a kid who’d never been given half a chance, he told the school president and principal, making the case for a very large exception to their typical admissions process. The principal, Steve Simpson, felt stirrings of sympathy and issued Oher a challenge: get his grades up in another private school and he could enter the far more prestigious Briarwood the next semester.

Within a few months, Simpson had a change of heart and admitted Oher to his school. But entering Briarwood was no panacea and produced no immediate change. The kid was out of place, shy, awkward and way behind.

This is where the movie and real life began to diverge. In reality, Oher couch-surfed at the homes of his fellow students and foster families for his first few years at school and played three sports — basketball, track and field and football — before ever meeting the Tuohy clan in 2003. In the movie, Oher — played by Quinton Aaron — is fully homeless and has nothing to do with athletics until the very wealthy and generous family took him in.

The Tuohys are conservative Christians and taking Oher in raised eyebrows in their community, but it was quickly a natural fit, even if it didn’t go exactly the way the movie suggested.

In The Blindside, Bullock plays Leigh Anne Tuohy, the outspoken matriarch of the family and wife of Sean Tuohy (Tim McGraw), a former college basketball star and wealthy fast food entrepreneur. The movie posits that their young son S.J.’s mismatched schoolyard friendship with Oher is the catalyst for their involvement in his life, while in reality, it was actually Sean noticing Oher on the sidelines at the gym that prompted their involvement.

It’s a minor point, but one that cascades throughout the movie and led to Oher’s big disagreement with how his story played out on the big screen. Just as in real life, the fictionalized Oher ultimately becomes a force of nature in high school football, but how that happened and the timeline his development followed was a real bone of contention.

“I felt like it portrayed me as dumb instead of as a kid who had never had consistent academic instruction and ended up thriving once he got it,” Oher wrote in his 2014 memoir, I Beat the Odds. “Quinton Aaron did a great job acting the part, but I could not figure out why the director chose to show me as someone who had to be taught the game of football. Whether it was S.J. moving around ketchup bottles or Leigh Anne explaining to me what blocking is about, I watched those scenes thinking, ‘No, that’s not me at all! I’ve been studying — really studying — the game since I was a kid!’ That was my main hang-up with the film.”

Soon after Sean first met Oher, he set up a standing cafeteria account for him so that he’d be able to eat lunch every day. Eventually, on Thanksgiving weekend, the family crossed paths with Oher, who was walking alone in the rain, wearing his only pair of shorts and going nowhere in particular. They took him in for the weekend, an arrangement that soon became permanent.

A tutor was hired. New clothing was purchased. Leigh Anne told The New York Times point blank that she was raised by a racist father to be a racist herself, but she’d moved past that retrograde upbringing by the time she’d grown up and had children of her own, including a daughter named Collins, who was in high school at the same time as Oher. After some early awkwardness, Oher became a full-fledged member of the Tuohy family.

Football scouts crisscross the nation looking for top talent, putting hundreds of thousands of miles on their cars as they pull into towns that are off-the-beaten-path based on an odd report or rumor about a young kid with some talent. Given his lack of formal education or athletic training, Oher had virtually zero reputation when he began playing football at Briarcrest, but that changed soon enough — once he polished his game on the football field, it became clear that he was special.

Universities across the South showed up during the spring of 2004, hoping to recruit him. Prominent coaches later appeared in the movie as themselves, underscoring the huge interest in Oher’s potential. He was a First Team Preseason All-American at left tackle, perhaps the most important non-quarterback position on the offensive side of the ball.

Oher was closer with the head coach, Hugh Freeze, than the movie suggests, having spent plenty of time with him and his family both on and off the field. He even once said Freeze’s daughters were “like my sisters,” a sign of just how many families were eager to take him in. (Freeze later resigned as head coach of Ole Miss after a personal scandal, though Oher had his back then, too.)

Both Tuohys had gone to the University of Mississippi, which complicated Oher’s decision to follow in their footsteps, at least in the eyes of the NCAA. His academic record, spotty at best given his years of struggles and lack of schooling, also made it difficult for him to initially attend the school. But with some correspondence courses and tutoring, he was able to raise his grades enough to earn his degree and earn admission into the school.

He was an instant success — First Team Freshman All-American his first year, Second and then First Team All-SEC in his sophomore and junior years, and finally a First-Team All-American in his senior year in 2008.

By that point, his backstory wasn’t at all relevant to his playing skills, which clearly stood on their own. Lewis’ book was published in 2006, while the movie hit theaters in 2009, just after Oher was drafted in the first round (23rd overall) by the Baltimore Ravens.

If anything, the attention from the movie grew to frustrate him during his career. Making the NFL and sticking in the league is hard enough without the added pressure of a mega-hit, Oscar-winning movie about your life to draw international attention to your rookie season.

The movie would continue to follow him throughout his career, which had its ups and downs. Making it to the NFL is remarkably difficult and staying in the league more than a few years is exceedingly rare — careers average just a shade over three years, and not all of that time, if any, is generally spent as a starter on a winning team.

“People look at me, and they take things away from me because of a movie,” he said in 2015, near the end of his career. “They don’t really see the skills and the kind of player I am. That’s why I get downgraded so much, because of something off the field. This stuff, calling me a bust, people saying if I can play or not … that has nothing to do with football. It’s something else off the field. That’s why I don’t like that movie.”

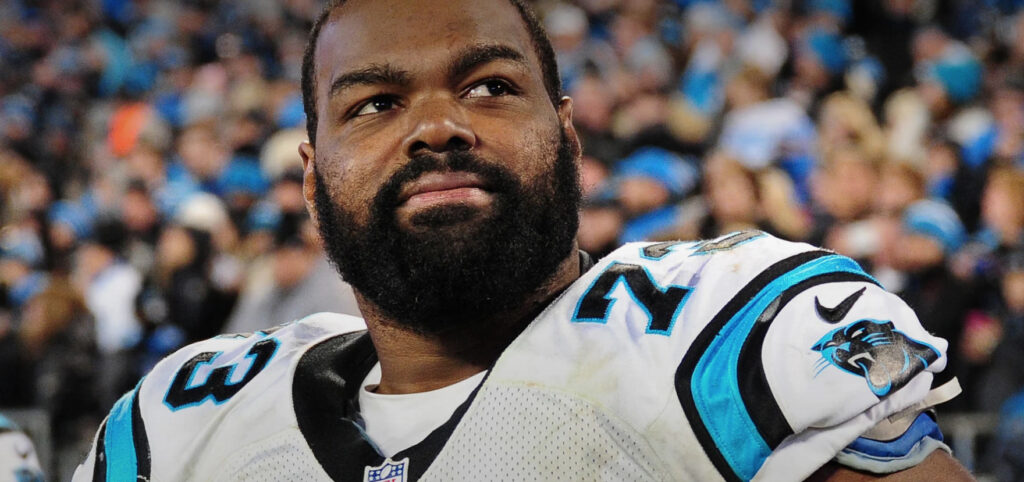

It’s not that he didn’t have his successes, of course — Oher won a Super Bowl as a starter on the Ravens in 2013 and went to another Super Bowl in 2016. He played eight years in the NFL, which is a great career for anyone, much less someone who came from his background. The Ravens got more than they could have ever wanted from a late first-rounder.

Ultimately, Oher was released by the Carolina Panthers in the summer of 2017 due to his trouble with post-concussion syndrome, which ultimately wound up marking the end of his career in the NFL. He is now a public speaker and advocate.